Hello Dear Reader,

In this next publication of Flint and Steal we shall be exploring one of the worst instances ever to befall Greece. It would mark the end of ideas, ideals, and freedoms of many kinds. Today, we will cover not just a single event but an entire conflict, the Peloponnesian War. So come come dear reader, take a seat around my fire and let us begin. The Athenians and the Spartans begin to march with merciless and menacing intentions.

A Fickle Fate

It is a fickle fate that throughout history, when a country falls or fails, there is one reason why and that is usually the country itself. Now, of course there are such things like foreign invasions, disease, or global economic disasters that certainly do not help but it is the nation’s reaction to the these events that define it. I say this to set the scene.

Seemingly almost immediately after the Athenians and the rest of the Greeks had defeated and won their momentous victory against the Persian Empire, they decided to fight themselves. Why did they not take a victory lap, unify as one Greek state, and prosper in peace together? Well, dear reader, an excellent question! My answer to that is it would be too easy. Humans are born naturally wanting and yearning for conflict. So, when you defeat the enemies from far away, you search for the enemies close by.

The Lost Leagues

To add further context, this war was not just between Athens and Sparta but rather large regions and cities allied with them. The forces allied with Sparta were called the Peloponnesian League while the forces allied with Athens were called the Delian League. I invite you to confer with the map below to see who precisely held what. Athens and her Delian League can be shown in red while Sparta and her Peloponnesian League can be shown in blue.

Now, there are some that would call this conflict a civil war, but other argue against it. As many country borders in antiquity were fluid or did not exist at all, I believe both points of view may be correct. Regardless, this war began in the year 431 B.C. and concluded in 404 B.C. It is important to note, however, that this was not 30 years of fighting at once. The fighting was staggered with treaties being signed and then those said treaties being eventually broken to continue the conflict.

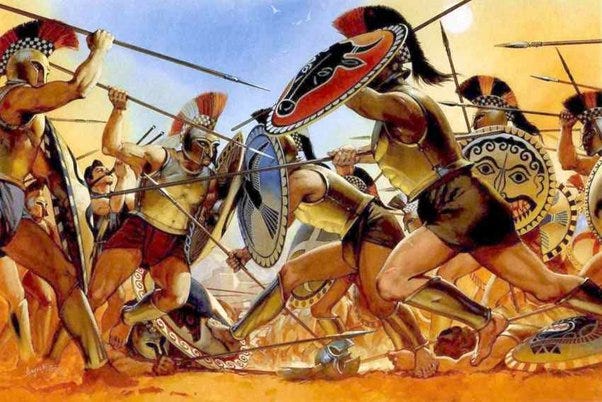

A most important point that am required to make here is that both sides held their strengths in different contexts and respects. The Spartans were a legendary force to be reckoned with on land. Their warrior culture helped put to waste their enemies wherever they were to be found. However, in stark contrast, the Athenians held their strength with naval power. They had a robust alliance of tribute paying islands that helped support their small but mighty empire. Their difference in military might was a consequential reason why this war went on for so long. How may you ask? A terrific question dear reader! Well, to put it simply, the two armies were never willing to fight in high pitched battles against one another directly because they would lose if they fought on the opposing enemy’s terms. Instead, as we will find, it was an attempt to out maneuver ones enemy that included a series of proxy battles. Eventually, however, there would be a direct battle between the two empires that would prove decisive in the end.

The Archidamian War

The Archidamian War, the first pivotal phase of the Peloponnesian War, reveals some quite intricate dynamics that would shape the rest of the conflict. At its outset in 431 B.C., the Spartan strategy, led by King Archidamus II, aimed to weaken Athens through annual land invasions. They intended to keep Athens from accessing its land around the city that was used for farming and thus, secure a victory. However, they would need to do little as Sparta would find an infamous ally.

A devastating outbreak of a catastrophic plague in Athens in 430 B.C., would prove to be detrimental to any immediate Athenian war efforts by destroying approximately one-third of the city's population. This threw Athens into disarray and caused Athens to lose many of its soldiers and sailors, crippling its military strength. In the face of this overwhelming catastrophe, the Spartans found themselves in a unique position with a unique ally. They could have pursued their advantage, further pressing their campaign to conquer Athens, but they did not. There was no need to. They, instead, recognized the dangers of contagion and chose to step back, allowing the plague to take its toll on the Athenians, a decision that would have significant repercussions for the war's unfolding, as the Spartans chose to save their men and army rather than pursue final victory. This would be the correct course of action as it would save the Spartan army for further battles in the future.

However, Athens was not out of the fight yet as Demosthenes would secure a victory over the legendary Spartans in the Battle of Pylos in 425 B.C. One of the reasons for this great victory was the Athenian attraction of helots. What is a helot? Well, another great question. Helots were Spartan slaves that tended Spartan fields while its citizens were training for war and were away at war. See, runaway Helots were gathering at Pylos and the Spartans, in fear of a revolt, decided to march on the post to secure their position. Demosthenes knew this and used this knowledge to trap a force of 300 Spartans on Sphacteria, thus, quelling the notion of Spartan invincibility.

As both sides grew tired of hostilities and needing recovery, the Peace of Nicias was declared. However, dear reader, it's important to note that this "peace" was more akin to a cessation of fighting between Athens and Sparta, rather than a genuine harmonious resolution. This is due to each respective side holding their hatred toward the other as neither side could gain a foothold over the other in the overall war. The Athenians, whose blood could still be described as hot, remained focused on strengthening their position. Amid this fragile pause, an unfortunate city found itself caught in the center of the conflict: Melos, a neutral city that had wisely refrained from taking sides in the prior war. Regrettably, Athens perceived this neutrality as a certifiable affront to its existence. In the summer of 416 B.C., under the banner of the Peace of Nicias, Athens delivered a stark ultimatum to Melos: align with Athens or face annihilation. Melos, resolute in its stance, rejected the ultimatum, prompting Athens to lay siege to the city. By the winter's end, Melos had fallen, its adult male population killed, and the women and children subjected to slavery. I believe that this stark demonstration of Athenian power, during the so-called "peace" of Nicias, was a show of weakness. They would not have needed to lay siege to a neutral city but it seems as if they needed a win, so to speak.

The Sicilian Disaster

Grasping at redemption, the Athenians decided to mount an expedition to Sicily. At the heart of this conflict lies a web of alliances. See Athens had Ionian allies on the Isle of Sicily and Sparta had Dorian allies in Syracuse, on the Isle of Sicily. To put this in further context, Ionian and Dorian are ethnicities. So, in the wake of their defeat, the Athenians wanted to strengthen their hold on the territory that they still held. Defeating the Spartan backed Dorians seemed like an excellent way to achieve a victory. How wrong they would be.

The Athenian force, under the joint leadership of Alcibiades, Nicias, and Lamachus, comprised of around 134 ships and approximately 5,100 hoplites, making it one of the largest military expeditions in Greek history. However, the campaign rapidly turned into a protracted and certifiably disastrous ordeal. The Athenians faced not only the military might of Syracuse but also political divisions within their own leadership.

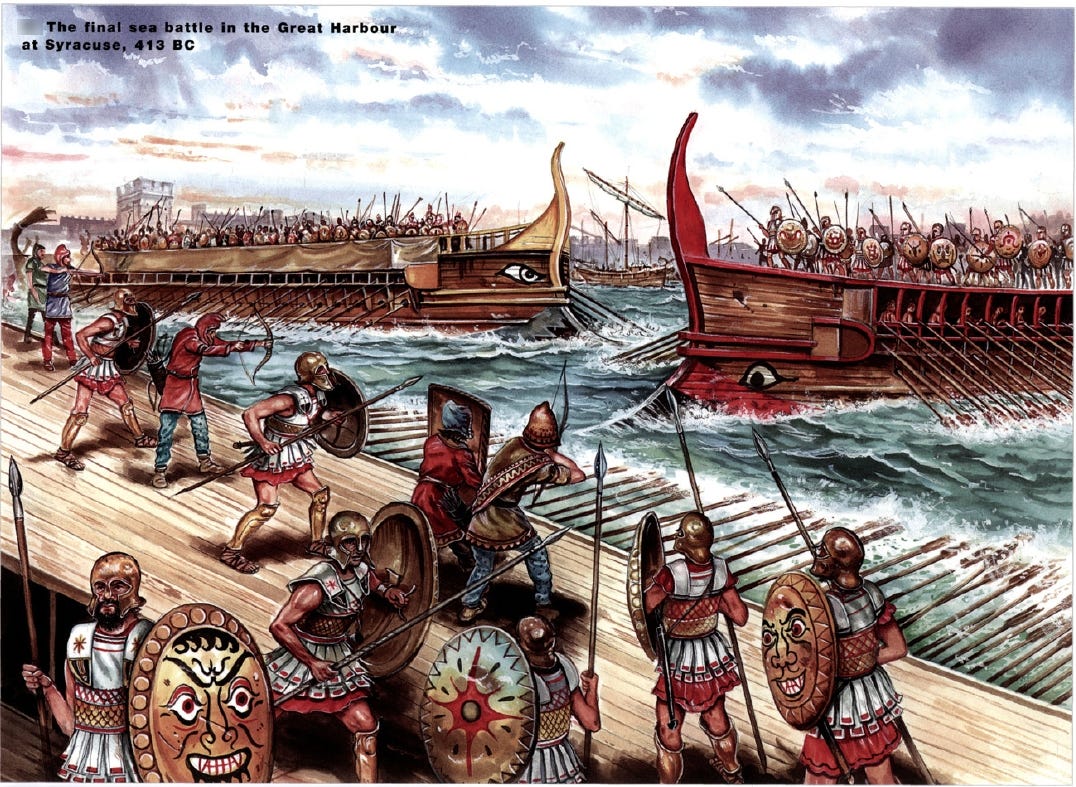

The most significant battle of the Sicilian Expedition was the Siege of Syracuse, a dramatic and fiercely contested struggle. The Syracusans, led by the capable general Gylippus, managed to withstand the Athenian assaults and launched a counteroffensive. The Athenian fleet suffered a devastating defeat in the harbor of Syracuse, losing a significant portion of their ships. Reinforcements from Athens failed to turn the tide, and the Athenians found themselves trapped and eventually destroyed.

The protracted and unsuccessful campaign in Sicily led to a catastrophic loss for Athens. Many of their soldiers were killed or captured, and their fleet was severely weakened. Athens' imperial ambitions were severely hampered, as the Sicilian Expedition drained valuable resources and manpower. The defeat in Sicily had far-reaching implications for Athens, leaving the city vulnerable to Spartan resurgence and reshaping the balance of power in the Peloponnesian War.

The Decelean War

The third and final phase of this conflict produced an interesting ally that surprised both sides, at least an ally of Sparta. However, dear reader, I will keep you in suspense as it is not yet time to bring them to the stage. At the beginning of this war, it was once again Athens that seemingly had the upper hand. From 410-406 B.C. Athens would recover much of its lost empire.

Not to be outdone, the Spartans went looking for an ally or rather an ally came looking for them. This ally brought some military support but more importantly they brought financial support. Remember, dear reader, Athens ruled the seas so they had a robust trade alliance that helped them make significant financial gains. The tribute paying islands also come back into the story as we must remember their financial contributions to Athens in the form of tribute. At this point in the story, it is my pleasure to reintroduce the Persians. Never one to forget the Athenians, the Persians would back the Spartans in a definitive and killing blow to Athens.

Under the command of the Spartan admiral Lysander, the Spartan fleet succeeded in establishing a fortified naval base at Decelea in northern Attica, with the help of Persian resources. This location provided a strategic advantage, as it allowed Sparta to maintain a more extended naval presence in the eastern Mediterranean and cut off vital Athenian grain supply routes.

One of the pivotal naval engagements of the Decelean War was the Battle of Notium in 406 B.C. This battle saw the Athenian fleet, commanded by Alcibiades and Thrasybulus, suffer a significant defeat at the hands of Lysander. The defeat at Notium weakened the position of Alcibiades, who had been a prominent Athenian general, and proved a critical setback for Athens.

In 405 B.C., the Decelean War reached its climax with the decisive Battle of Aegospotami. Lysander, with Persian support, confronted the Athenian fleet under Admiral Conon. The Spartan fleet achieved a victory, no less than stunning, by capturing or destroying almost the entire Athenian fleet. This defeat crippled Athens' naval power and effectively sealed its fate. Following this devastating loss, the Spartans laid siege to Athens, leading to the city's eventual surrender in 404 B.C.

The surrender of Athens marked the end of the Peloponnesian War, with the terms of the peace negotiated in Sparta's favor. Athens was forced to dismantle its Long Walls, reduce its navy to a mere twelve ships, and cede its overseas possessions, effectively ending its imperial ambitions. The Decelean War had brought the conflict to a decisive conclusion, reshaping the balance of power in ancient Greece and establishing Sparta as the dominant city-state.

The Peloponnesian War, including its final phase in the Decelean War, remains a compelling tale of ambition, conflict, and shifting alliances, leaving an enduring legacy in the annals of ancient history.

A Motif

The motif, dear reader, that we have come to discover as we delved into this war is death and destruction. Not just the death of Greek forces on the side of the Athenians or Spartans but the death of ideals. Unfortunately, with the defeat of Athens, the Greek Golden Age came to an end. The country and its vast, revolutionary ideas of democracy and freedom would be destroyed, at least for a time. To add insult to injury, Sparta would force a tribute to be paid and the legendary city state would be under the control of 30 leaders of Sparta’s choosing.

Eventually, the “Thirty Tyrants” would be overthrown and a democracy would be restored. However, this would matter little as the city states would continue to change and the idea of a united Greece would take hold a few decades later. It was under the leadership of King Philip II of Macedonia that these rivalries among the Greek city-states found their end. King Philip orchestrated the unification of nearly all of Greece, a feat that ultimately excluded only Sparta from this consolidation. It was left to King Philip's son, the legendary Alexander the Great, to later subjugate Sparta, solidifying the Macedonian Empire's hold over the entirety of Greece.

Fortunately, for lovers of history like us, we will soon see a new power rise in the West. A power that will forever alter the history of the planet. Whether it would be for the best or the worst, I will leave for you to decide.

Well, dear reader, it seems like the Spartans march home as the light of Athens glory finally fades. Please let me know what you think of this publication as it was the first time I covered an entire conflict in total. Join me next time where we will be delving into a rebellion that would shock the Romans and bring about an end to their dominance in the north.