Hello Dear Reader,

Today we cover the second and final part of the Second Punic War between Rome and Carthage. In our previous publication, we formerly covered the major figures and events leading up to the war. Today we will cover the fighting and those who brought about this bloodshed. So come, dear reader, take a seat around my fire and let’s begin. The elephants trumpet, the men march, the wind howls across the Alps and Rome is in peril. She will not submit.

Part 2: Cheaters of Death

Cold Revenge Against the Romans

The Second Punic War was defined by a series of brutal and strategically complex battles fought across Italy, Hispania, and North Africa. Unlike the First Punic War, which saw Rome adapting to naval warfare, this conflict would test its resilience on land against one of history’s greatest military minds: Hannibal Barca. From the outset, Carthage’s bold strategy of invading Italy itself put Rome on the defensive, forcing it into some of the most devastating defeats in its history. Yet, through sheer determination, strategic brilliance, and the emergence of leaders like Scipio Africanus, Rome would ultimately turn the tide. Our battles begin below.

Battle of the Ticinus (218 B.C.)

The Battle of the Ticinus was the first major engagement of the Second Punic War, marking the initial clash between Hannibal’s army and the Roman Republic. Having successfully crossed the Alps, Hannibal advanced into northern Italy, where he encountered the Roman forces led by Publius Cornelius Scipio, father of the future Scipio Africanus. The battle took place near the Ticinus River, with the Romans fielding a force composed largely of cavalry, supported by light infantry, while Hannibal relied on his elite Numidian cavalry, known for their speed and hit-and-run tactics. Confident in his army’s ability, Scipio engaged Hannibal without properly assessing the situation. Hannibal, however, executed a swift and aggressive cavalry assault, overwhelming the Romans and putting them on the defensive. The superior maneuverability of the Numidians quickly turned the battle in Hannibal’s favor, and the Roman cavalry, unable to withstand the assault, was thrown into disarray. In the chaos, Scipio himself was wounded and nearly captured, but his son, the young Scipio Africanus, courageously rescued him and helped him escape. The battle ended in a decisive Carthaginian victory, forcing the Romans to retreat and allowing Hannibal to advance deeper into Italy unopposed.

Battle of the Trebia (218 B.C.)

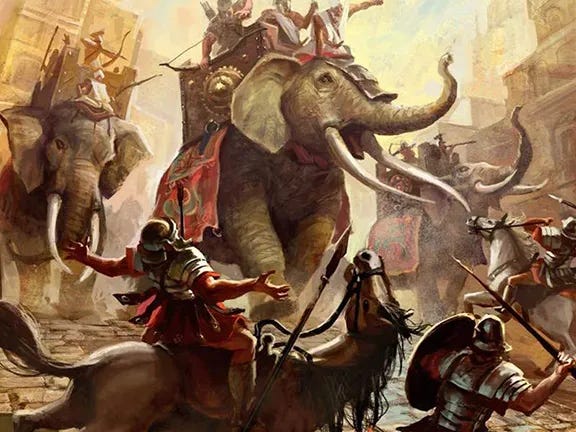

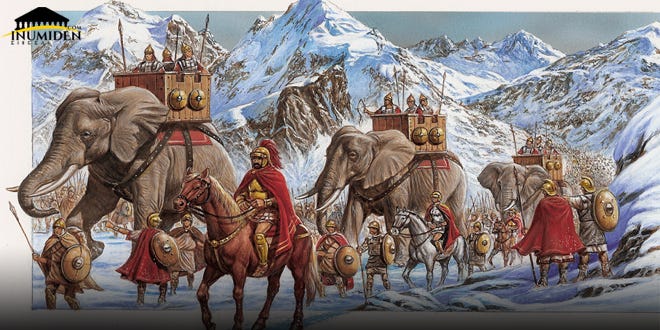

Fresh from his victory at Ticinus, Hannibal moved southward and encountered a second Roman army under Tiberius Sempronius Longus, who was eager to confront him. Hannibal, a definitive master of warfare, devised a strategy to lure Sempronius into a trap. Using his Numidian cavalry to harass the Roman camp, he provoked Sempronius into launching a reckless attack without properly preparing his troops. The Roman army, consisting mostly of heavily armored infantry, was forced to cross the icy-cold waters of the Trebia River early in the morning, weakening them before the battle even began. Hannibal’s well-rested forces, including his 37 war elephants, Iberian infantry, and highly mobile cavalry, were strategically positioned to outmaneuver the Romans. As the two armies clashed, Hannibal sprung his hidden reserve force, led by his younger brother Mago Barca, from their concealed position. The ambush struck the Romans from behind, collapsing their formation and throwing the entire army into chaos. The Romans, now trapped between the river, Hannibal’s main army, and the hidden attackers, suffered a devastating defeat. Thousands were cut down, while the survivors either drowned trying to escape or were captured. The battle confirmed Hannibal’s military genius and inflicted a severe psychological blow to the Romans, proving that Hannibal was not merely an invader but a formidable commander capable of annihilating entire legions.

Battle of Lake Trasimene (217 B.C.)

Hannibal continued his march southward, aiming to spread destruction across Italy and break Roman morale. His next major engagement took place near Lake Trasimene, where the Roman commander, Gaius Flaminius, sought to stop him. Flaminius, eager for battle and impatient to strike at Hannibal, led his army into a narrow valley along the lake’s edge without conducting proper reconnaissance. Unbeknownst to him, Hannibal had positioned his forces on the hills overlooking the valley, hiding them behind ridges and dense fog. As the Roman army marched through the confined space, Hannibal unleashed his forces in a ferocious ambush, trapping the Romans between the lake and the surrounding hills. The Romans, unable to maneuver or form proper battle lines, were slaughtered in a merciless onslaught. Hannibal’s forces attacked from all sides, cutting down the Romans before they had a chance to organize a defense. Flaminius himself was killed in the melee, and nearly 15,000 Roman soldiers perished. Many of those who tried to flee drowned in the lake, while others were captured. The crushing defeat at Lake Trasimene sent shockwaves through Rome, prompting the Senate to abandon traditional military strategies and appoint Quintus Fabius Maximus as dictator, who would adopt a strategy of attrition rather than direct confrontation with Hannibal.

Battle of Cannae (216 B.C.)

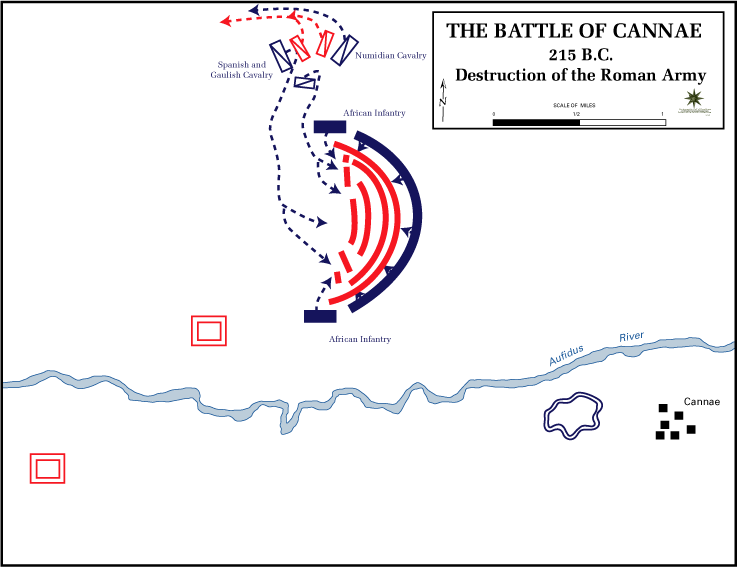

The Battle of Cannae remains one of the most studied and celebrated battles in military history, a testament to Hannibal’s strategic brilliance. After his victories at Trebia and Lake Trasimene, Hannibal continued his campaign in Italy, drawing the Romans into a decisive confrontation. The Roman Senate, eager to crush Hannibal once and for all, assembled the largest army Rome had ever fielded up to that point, numbering nearly 86,000 troops under the joint command of Lucius Aemilius Paullus and Gaius Terentius Varro. Hannibal, vastly outnumbered with an army of about 50,000 men, relied on superior tactics rather than brute force.

Positioning his forces in an unconventional crescent formation, Hannibal placed his weaker Iberian and Gallic infantry in the center while his elite African veterans held the flanks. He deliberately allowed the Romans to push into the center, creating the illusion of a retreat. As the Roman legions pressed forward in their tight formations, they unknowingly fell into Hannibal’s trap. The crescent slowly collapsed inward, and at the perfect moment, the Carthaginian flanks—composed of hardened African troops—swung around and enveloped the Romans on all sides. At the same time, Hannibal’s Numidian cavalry, led by Maharbal, routed the Roman horsemen and struck the rear of the Roman army, completing the encirclement.

What followed was a massacre of unprecedented scale. The Roman army, trapped with no room to maneuver, was cut down systematically. Soldiers, unable to fight effectively in the crush of bodies, were slaughtered where they stood. By the end of the battle, between 50,000 and 70,000 Romans lay dead, including Aemilius Paullus, consuls, senators, and some of the finest soldiers in the Republic. Cannae was a catastrophic defeat for Rome, leaving the city in a state of despair. Yet, despite this egregious disaster, Rome refused to surrender, choosing instead to adopt a strategy of attrition against Hannibal rather than risk another direct confrontation.

Siege of Syracuse (214–212 B.C.)

While Hannibal ravaged Italy, Rome sought to regain control of the strategic city of Syracuse, which had allied with Carthage. The Roman general Marcus Claudius Marcellus, known as "The Sword of Rome," led the siege against the city, facing fierce resistance. Syracuse was not an ordinary city; its defenses had been strengthened by the genius of Archimedes, the famed Greek mathematician and inventor. Using a variety of advanced siege defenses, Archimedes devised catapults capable of hurling massive projectiles at Roman ships, enormous claw-like cranes to overturn enemy vessels, and even mirrors rumored to have focused sunlight to ignite Roman ships.

Despite these formidable defenses, the Romans maintained their blockade, starving the city into submission over two years. In 212 B.C., Marcellus launched a final assault, breaching the city walls and capturing Syracuse. In the chaos, Roman soldiers looted the city, and in defiance of Marcellus’ orders, a Roman soldier killed Archimedes as he worked on a mathematical problem. The fall of Syracuse marked a major victory for Rome, securing control over Sicily and cutting off Carthage from one of its key allies.

Battle of the Metaurus (207 B.C.)

By 207 B.C., Hannibal’s fortunes had begun to wane. His greatest hope for reinforcement lay with his brother, Hasdrubal Barca, who had raised a powerful army in Spain and marched toward Italy to join forces with him. If the two brothers could unite, Rome would be in grave danger. However, Roman intelligence intercepted Hasdrubal’s courier, revealing his planned route. Acting swiftly, Gaius Claudius Nero and Marcus Livius Salinator led their armies to intercept Hasdrubal at the Metaurus River before he could reach Hannibal.

The battle began with the Roman forces initially struggling against Hasdrubal’s well-organized Carthaginian troops. However, Nero, recognizing a weak point in Hasdrubal’s flank, took a daring gamble. He redeployed his best troops from another section of the battlefield and led them in a surprise attack against the Carthaginian right flank. The sudden assault threw Hasdrubal’s army into disarray, and as the Romans pressed their advantage, the Carthaginian lines collapsed. Hasdrubal, realizing the battle was lost, rode into the fray and perished alongside his men. His severed head was later thrown into Hannibal’s camp as a grim message—his long-awaited reinforcements would never come. The defeat at Metaurus shattered Hannibal’s last hope of receiving substantial aid, forcing him into a defensive position in Italy.

Battle of Ilipa (206 B.C.)

While Rome fought Hannibal in Italy, Publius Cornelius Scipio, the son of the slain Scipio at Ticinus, had risen to prominence in Spain. Determined to expel the Carthaginians from the Iberian Peninsula, Scipio faced a combined Carthaginian army under Hasdrubal Gisco and Mago Barca near the town of Ilipa. The two sides engaged in a series of skirmishes before Scipio devised a bold strategy to outmaneuver his foes.

Each day leading up to the battle, Scipio deployed his troops in a predictable formation, keeping his best troops, which were the veteran Roman legions and their Iberian allies, in the center. The Carthaginians, expecting another routine engagement, mirrored this setup. However, on the day of battle, Scipio reversed his formation, placing his strongest troops on the wings and his weaker forces in the center. When the battle began, Scipio held back his center and unleashed a devastating flanking attack. The Carthaginian center, which had been used to holding the Roman legions at bay, suddenly found itself unsupported as the Roman wings crushed the enemy’s flanks. The Carthaginian army crumbled under the relentless assault, and thousands were slaughtered or captured.

Ilipa was a masterclass in deception and tactical brilliance. With this victory, Spain was permanently lost to Carthage, and Rome secured a valuable stronghold that would later provide the manpower and resources for Scipio’s invasion of North Africa.

Battle of Zama (202 B.C.)

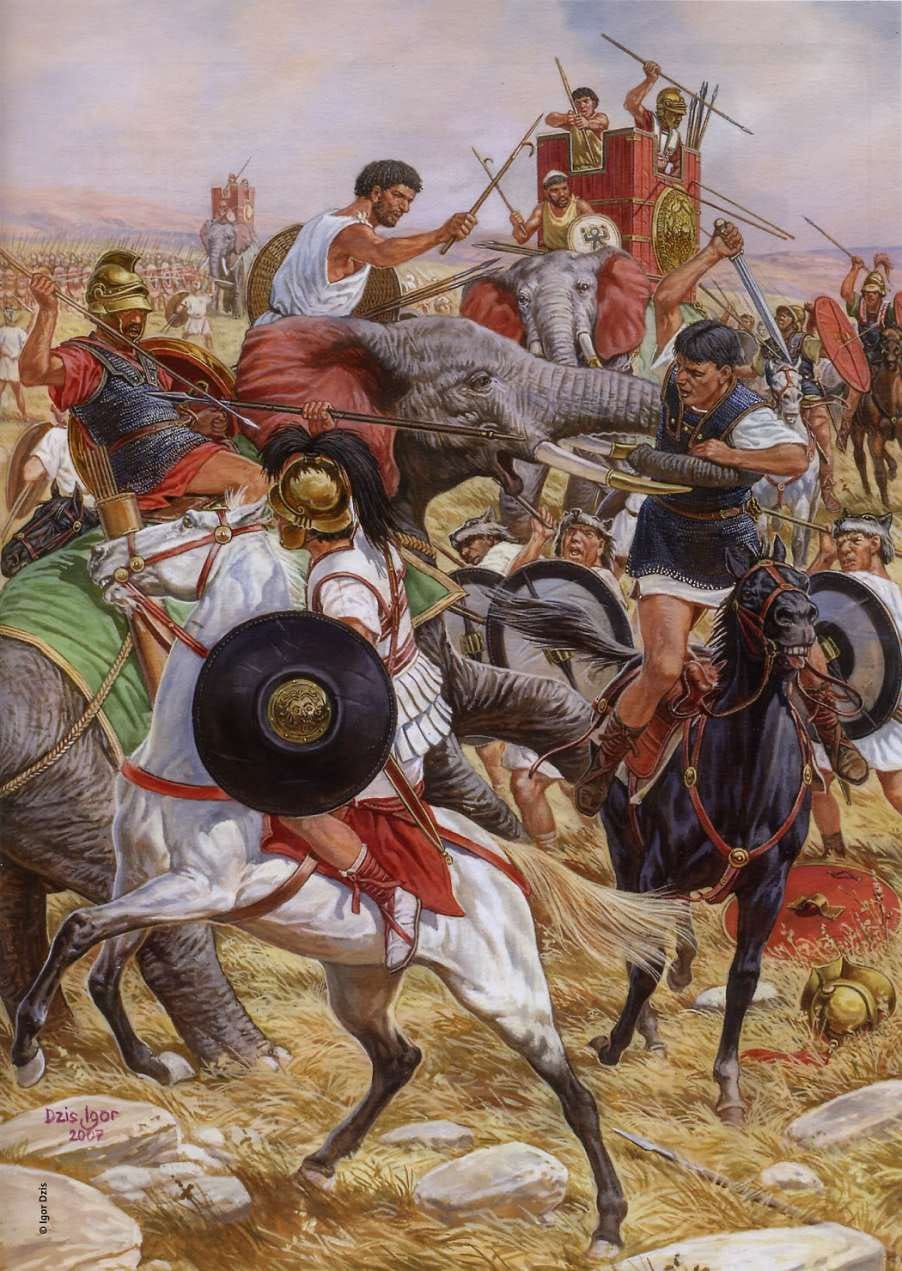

The climactic battle of the Second Punic War took place in North Africa, where Scipio Africanus, now a seasoned commander, faced Hannibal himself for the first and final time. After securing Spain and forging an alliance with King Masinissa of Numidia, Scipio forced Carthage to recall Hannibal from Italy to defend the homeland. The two armies met at Zama, with Hannibal commanding war elephants, Carthaginian infantry, and an elite corps of veterans from his Italian campaigns.

Hannibal launched his elephants in a massive charge, hoping to break the Roman lines. However, Scipio had anticipated this and ordered his troops to open gaps in their formation, allowing the elephants to pass harmlessly through while being cut down from the sides. The battle then turned into a brutal infantry clash, with neither side gaining a clear advantage. The tide turned when Masinissa’s Numidian cavalry, having routed the Carthaginian horsemen, returned to strike Hannibal’s rear, sealing the fate of the Carthaginian army.

Hannibal, recognizing defeat, fled the battlefield, while his army was annihilated. The loss at Zama forced Carthage to surrender unconditionally. Rome imposed harsh terms, stripping Carthage of its overseas territories, disbanding its navy, and demanding crippling war reparations. The Second Punic War had ended, marking the rise of Rome as the dominant power of the Mediterranean and the decline of Carthaginian influence.

The Final Blow: The Road to the Third Punic War

Though Carthage had been stripped of its empire and forced into submission, the city proved remarkably resilient. In the decades following the Second Punic War, Carthage rebuilt its economy, focusing on trade and agriculture. However, despite fulfilling its treaty obligations, Carthage remained under the shadow of Rome’s suspicion and hostility. Roman statesmen such as Cato the Elder viewed Carthage’s recovery as a threat, famously ending his speeches with the ominous phrase: "Carthago delenda est"—Carthage must be destroyed.

Tensions escalated when Carthage, desperate to defend itself from Numidian incursions, raised an army without Rome’s permission—an act the Senate deemed a violation of their treaty. Seizing the opportunity, Rome demanded Carthage’s complete disarmament and eventual destruction. When Carthage refused, Rome declared war, launching the Third Punic War.

Well, dear reader, we will stop their for now. The stage was set for Carthage’s final stand. In our next edition, we will witness the brutal siege of Carthage, a desperate last stand against Roman aggression that would decide the fate of the once-great city forever.

Yours Truly,

-Flint