Hello Dear Reader,

Today we cover the Third and final Punic War between Rome and Carthage. In the past few months we have covered the First and Second Punic Wars in which Rome emerged victorious in both. Today we will cover the Third Punic War, a war which would destroy one nation and leave the other utterly victorious. So come, dear reader, take a seat around my fire and let’s begin. The Romans launch their next assault upon the walls of Carthage and this time they have broken through. This time they will end it. There are some who say that Mercy is Cowardice and Rome has agreed.

Ever Wary

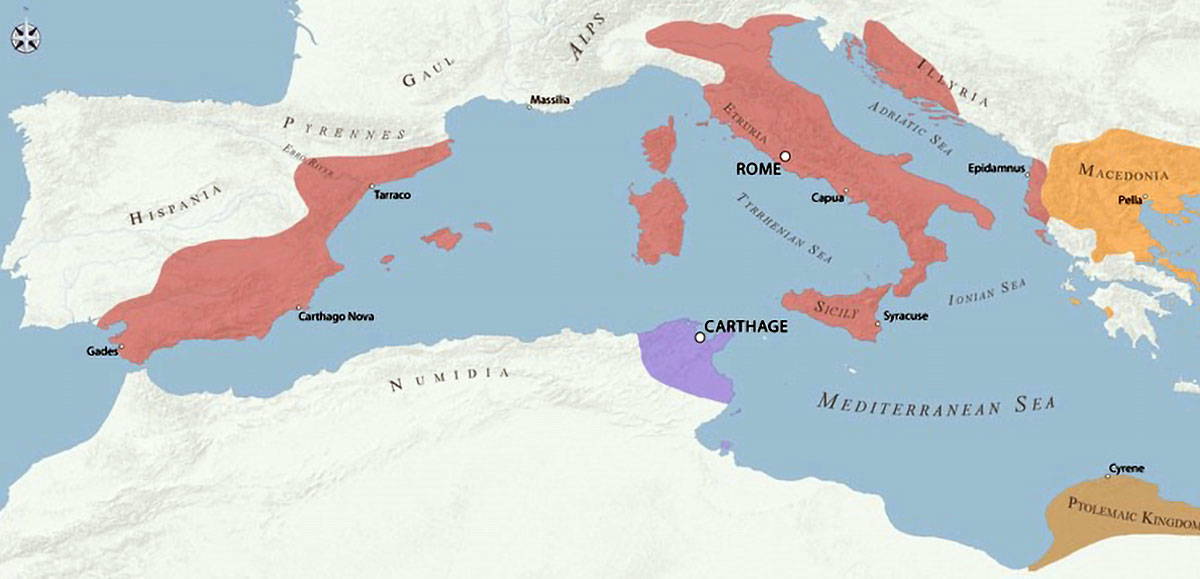

The Third Punic War was not a war of desperate defense or strategic conquest, it was more like an execution. Though a shadow of its former self, Carthage had begun to recover with its fields fertile, its ports humming, and its people continuing to survive. To Rome, this resurgence was intolerable. The memory of Hannibal still haunted the Senate chambers, and many feared that given enough time, Carthage might rise again. No voice was louder than that of Cato the Elder, who would famously state before the Roman Senate: Carthago delenda est—Carthage must be destroyed. Rome needed little excuse to act, and when one finally came, they seized it.

Justification

Carthage provoked Roman ire by defending itself against Numidian incursions. To note, these incursions had nothing to do with Rome itself but it gave Rome justification for war with Carthage. Why is this? Well, dear reader, let me refresh thy memory. The treaty that stopped the Second Punic War, had a clause in which the Carthaginians could not wage war, or raise an army, without permission from Rome. Now, Rome viewed that Carthage had technically broken this clause by defending itself against the Numidian incursions especially without Roman permission. The Carthaginians had raised an army and gone to fight the Numidian King. The campaign was a disaster and the Carthaginian army was annihilated but nevertheless, they had engaged in war. The offense was minor. To go and ask for permission to go to war while any enemy is at war with you, is ludicrous. Yet, Rome saw this as justification for war and seized the opportunity to forever remove a thorn from their side.

In 149 B.C., Roman legions landed in North Africa. Carthage, desperate and betrayed, offered complete surrender. But Rome demanded more. Carthage and its inhabitants were ordered to disarm and even to abandon the city entirely, resettling further inland—a demand the Carthaginians could not accept. With nothing left to lose, Carthage prepared for war, although, in truth, they had fallen into Rome’s trap. The Romans knew that if Carthage had nothing left to lose, they would make a last stand and Rome could destroy them once and for all.

The siege that followed was brutal and unrelenting, but to the credit of Carthage, they held out stubbornly behind their massive walls for nearly three years. Carthage’s defenses were formidable: 34 kilometers of walls, some parts triple-layered, reinforced by ditches, the sea, and the blood of the defenders.

The initial Roman siege, led by consuls Marcius Censorinus and Manius Manilius, struggled badly. The Romans could not fully blockade the city’s harbor, allowing Carthaginian blockade-runners to smuggle in crucial supplies. Carthaginian forces launched fierce counterattacks, setting Roman ships ablaze, destroying siege engines, and even pushing the besiegers back in skirmishes outside the walls. An epidemic struck the Roman camp during the sweltering summer of 148 B.C., compounding their misery and stalling their efforts.

In 147 B.C., desperate for progress, the Senate appointed Scipio Aemilianus, the adopted grandson of Scipio Africanus, to command. Scipio’s leadership turned the tide. He tightened the blockade and built massive siege works that included a giant mole to close off the harbor. This would be the final chokehold that would slowly strangle the city into submission. Starvation and disease spread inside Carthage’s walls and by the spring of 146 B.C., Scipio launched the final, apocalyptic assault.

Street-by-street, house-by-house, the Romans would fight bitterly against the last of the Carthaginian defenders. Fires raged uncontrollably through the city, and the screams of the dying filled the air. After six days of savage combat, only the citadel remained. When it too fell, Carthage was utterly destroyed. The survivors were enslaved, its once-great walls torn down, and its land symbolically cursed and salted.

Hegemony

With Carthage reduced to ashes and Corinth—another symbol of resistance in the Aegean—also destroyed in the same year, Rome stood alone as the unchallenged master of the Western Mediterranean. No rival navy sailed its seas. No foreign power dared challenge its legions. The republic, once a city of farmers and militia, had become an empire in all but name. Trade routes flowed freely to Rome’s ports, tribute poured into the Senate’s coffers, and Rome’s authority stretched from Hispania to the Aegean. Yet with dominance came decadence, and with victory came new enemies—not just of foreign descent, but also from within. But that, dear reader, is a story for another fire-lit evening. For now, know this: Rome had won the Punic Wars, and in doing so, had changed the fate of the ancient world forever.

Well, dear reader, it seems that the Romans have all loaded into their ships and have sailed away, leaving Carthage still burning in its wake. My greatest thanks for joining me around my fire. In our next publication, we will ride into the distant past, tracing the echoes of ancient tongues and forgotten bloodlines. We will uncover how language groups unlock the hidden paths of history and more importantly, the people behind them: the Yamnaya. They are a ruthless, warlike people who thundered across the steppes and carved their legacy into the bones of continents and the bodies that inhabited them. Through war, migration, and domination, they scattered their genes, their gods, and their way of life across the ancient world. What will be even more surprising to you, dear reader, I suspect, is how closely their shadow lingers still.

Until Next Time,

-Flint