Hello Dear Reader,

Today we look deep into the windswept steppe to a warlike people whose shadow still lingers in our blood, our language, and our bones.

Long before empires rose, before chariots thundered through the Near East or Latin echoed through Roman halls, the Yamnaya rode westward from the Pontic-Caspian plains. Their migrations reshaped continents, their tongue laid the foundation of the Indo-European family, and their genes ripple through the DNA of millions alive today.

So come, dear reader, take a seat around my fire and let’s begin. Hooves thunder across the steps and the first great shapers of our world have come to conquer.

The Indelible

Let it be acknowledged at the outset that much of what follows draws upon the venerable Steppe Hypothesis (Kurgan Hypothesis) — a theory which contends that the fountainhead of the Proto-Indo-European tongue and its attendant culture lies nestled in the boundless reaches of the Pontic-Caspian steppe, northward of the Black Sea. It is here, amidst sweeping grasslands now claimed by Ukraine, southern Russia, and western Kazakhstan, that the Yamnaya emerged — not as a mere ripple in the tide of prehistory, but as a something that can still be seen in our lives today.

Between the third and fourth millennia B.C., this formidable culture rose with suddenness and virility. The Yamnaya were the progeny of mingling: of eastern European hunter-gatherers interwoven with the highland folk of the Caucasus. From this alchemy was born a new race, statuesque, sinewed, and restlessly nomadic, fashioned by and for the endless horizon of the steppe.

Their very name, Yamnaya, is drawn from the Russian yama, meaning “pit,” a reference to the sunken graves they carved into the earth — solemn chambers over which they raised kurgans, or barrows, as monuments to the departed. These burial sites from the Black Sea to the Ural Mountains, often in solitary or small group interments, had grave goods like pottery, weapons, and animal bones. These are no longer just tombs, they are now monuments to giants.

They were pastoralists, moving with their herds of cattle and sheep. Their survival didn’t rely on walled cities or fields of grain, but on motion, adaptability, and an intimate knowledge of the land. The Yamnaya are among the first to have used horses and wagons extensively, making use of said horses and oxen to travel vast distances. This mobility, almost a superpower in the ancient world, allowed them to spread far and fast.

Warlike

The Yamnaya were, quite literally, giants among men — at least by the standards of their time. Archaeological and skeletal evidence suggests they stood significantly taller and more robust than many of their Neolithic neighbors, likely due to a protein-rich diet composed of meat and dairy. Some genetic studies indicate that the Yamnaya may have been among the first populations to exhibit lactase persistence, enabling them to digest milk into adulthood — a trait that would have provided a nutritional advantage in the harsh, resource-scarce environment of the steppe (please see my previous publication on ancient diets to learn more about food and its importance among different cultures).

This biological edge likely contributed to their physical dominance. In territorial disputes, their stature, mobility, and cohesion may have given them an upper hand. They raised cattle and sheep not only for sustenance, but also as portable wealth — and perhaps markers of social status within their society. It is plausible that their diet included not only beef and lamb, but even horse meat, reflecting a pragmatic approach to domesticated animals.

The domestication of the horse marked a turning point — not just for the Yamnaya, but for the trajectory of human civilization. Mounted on horseback or riding in wheeled wagons across the vast plains, Yamnaya warriors possessed a level of mobility and tactical range unknown to their contemporaries. To the settled Neolithic farmer, it is a terrifying concept. I invite you, dear reader, to imagine the sight of a towering, long-haired rider cresting the horizon. He is huge, muscle bound, riding a beast you do not recognize and you know he has come to take what you have, including your life. It is quite a sobering thought.

The Yamnaya's martial success and expansive movements did not end with their own culture. Their influence can be traced in the emergence and transformation of other Bronze Age civilizations, including the Corded Ware culture in Europe and the Andronovo culture in Central Asia. Through migration, conflict, and assimilation, they appear to have seeded a warrior tradition that would echo across continents for millennia.

A People in Stone

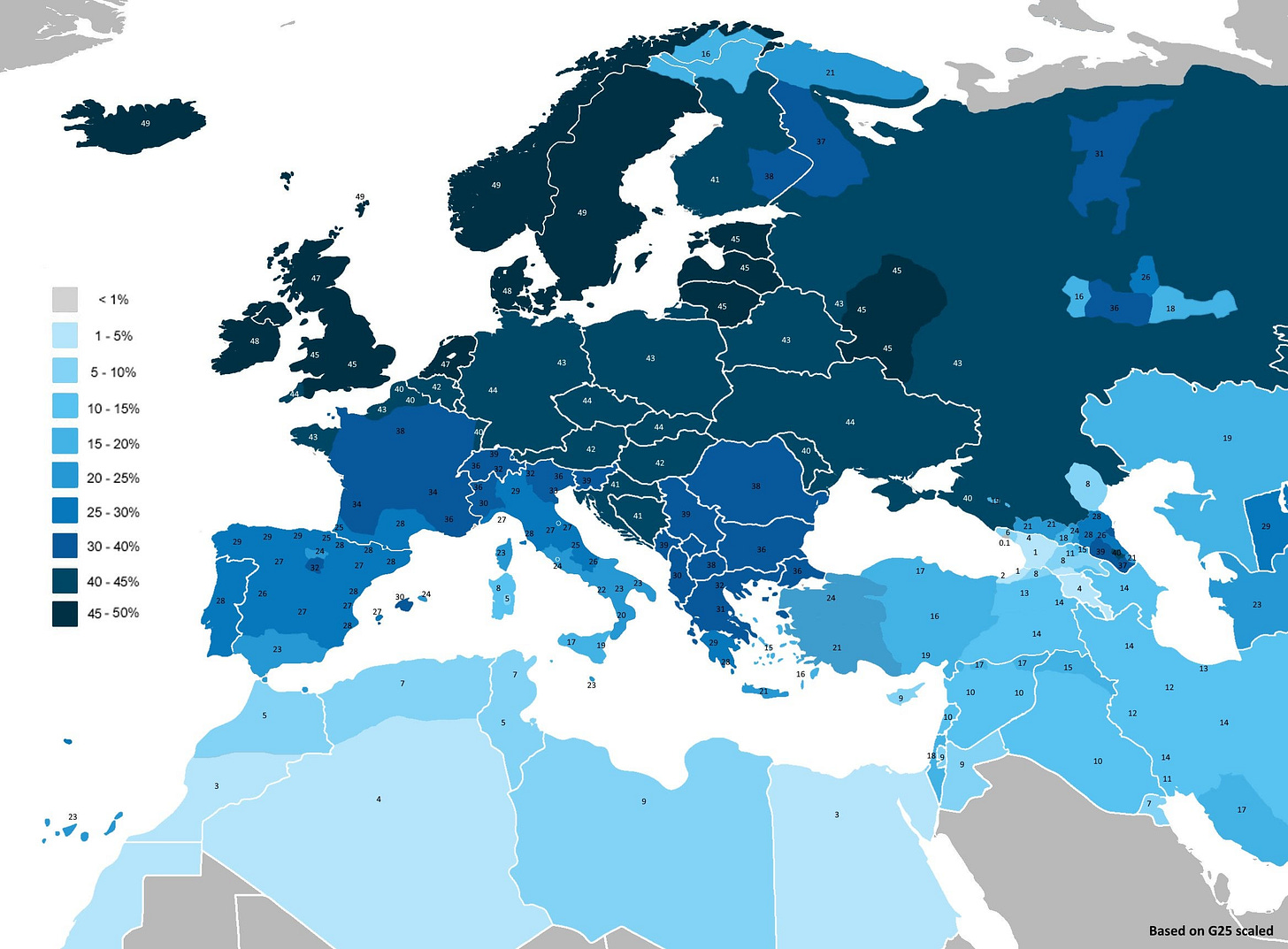

Recent advances in genetics have revealed the profound and enduring legacy of the Yamnaya across the European continent. Through a massive migratory wave during the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age, the Yamnaya left a significant genetic imprint—especially among the populations of Northern and Northwestern Europe. In some regions, up to 50% of the modern genome can be traced back to these ancient steppe pastoralists. Their DNA spread rapidly through cultures like the Corded Ware and Bell Beaker, blending with local Neolithic farmers and hunter-gatherers to form the foundational genetic makeup of contemporary Europeans. Traits such as height, lighter skin pigmentation, and even lactose tolerance — a relatively rare trait in early human history (and even today) — are partly attributed to Yamnaya ancestry. Today, this genetic signature persists not only in Europe but also in its diaspora, who came to the New World, conquering lands and cultures like their ancestors before them, bestowing their biological and cultural contributions upon the entire world.

In addition to their genetic legacy, the Yamnaya introduced specific haplogroups — particularly Y-DNA haplogroup R1b — which became dominant across much of Western Europe. R1b, rare before the Yamnaya expansion, now comprises the majority paternal lineage among populations in countries such as France, Spain, and the British Isles. This dramatic shift indicates not only large-scale migration but also social dominance, as the incoming Yamnaya lineages supplanted or absorbed earlier male lineages. Furthermore, genome-wide studies reveal that the arrival of the Yamnaya corresponded with major cultural upheavals and technological innovations, such as the widespread adoption of Indo-European languages, burial mounds (kurgans, as mentioned before), and early chariot warfare. Their influence was so transformative that some scholars refer to this period as a “genetic revolution” — one of the most significant in Europe’s deep history. From skeletal remains to living bloodlines, the shadow of the Yamnaya continues to loom over the genetic landscape of modern Europe.

Theoretically

The reach of the Yamnaya did not end in Europe. India, too, bears their imprint — not only in blood, but in language. Genetic and linguistic evidence suggests that Indo-Aryan migrations brought with them both physical ancestry and a sophisticated linguistic framework. This movement into the subcontinent stands as a compelling reaffirmation of the once-contested Aryan Invasion Theory.

The linguistic trail is particularly revealing. Core Proto-Indo-European words — such as ph₂tḗr (father), méh₂tēr (mother), bʰréh₂tēr (brother), and swésōr (sister) — find cognates in Sanskrit (pitṛ, mātṛ, bhrātṛ, svasṛ), just as they do in Latin, Greek, and Old English. This shared ancestry in language (albeit minor) underscores a vast and interconnected cultural diffusion, stretching from the steppes of Eurasia to the banks of the Ganges.

So, even though modern Indians speak Hindi, the deep linguistic roots of Hindi trace back through Sanskrit, which is an ancient Indo-Aryan language — and Indo-Aryan languages are a branch of the Indo-European family.

What’s more, the Yamnaya and their linguistic descendants likely did not assimilate immediately upon arriving in India. Instead, they appear to have maintained a degree of separation from the native Dravidian-speaking populations of the south. This social and genetic partition may have laid the foundations for the Indian Caste System, with the Indo-European-speaking elites preserving their dominance and often avoiding intermarriage. Over time, admixture occurred, but the echoes of this early stratification remain visible.

And tantalizingly, emerging research suggests the Yamnaya or their cultural descendants may have reached even as far as western China — though such theories await deeper archaeological and linguistic validation.

Fare Thee Well

Well, dear readers, it seems that the Yamnaya are galloping off into the sunset with their prizes of conquest in tow. I had a phenomenal time exploring the Steppes with such a phenomenal, indelible people (them and you).

In our upcoming publication, we’ll walk beside a warrior-philosopher cloaked in Roman Imperial Purple: Marcus Aurelius. Emperor, Stoic, and a thinker of a rare depth, his Meditations remain a practical example on how to use philosophy in our daily lives and the chaos that comes with it.. Together, we’ll ask: what can a man who ruled the known world teach us about ruling ourselves?

Until next we meet,

-Flint

![Sketches of Bell Beaker/Yamnaya warriors [Miguel Santos] : r/IndoEuropean Sketches of Bell Beaker/Yamnaya warriors [Miguel Santos] : r/IndoEuropean](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!MdUY!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F50ba1bee-89fa-40df-aa38-935e1780ed10_563x442.jpeg)

Great write up! I love mythologies because they are stories passed down through thousands of years, incorporating the previous legends and lore of that society. Ancient civilizations started from these migrant tribes, who decided to settle down and farm or continued their lives on the steppes. Imagine the stories of those who decided to break away from the group; any family fights or group conflict, some perhaps tired and settled down. I could go on, but to wrap it up, shit fascinates me.